Hello again!

I hope everyone’s summer is off to a fantastic start. I thought I’d take this opportunity to branch out a bit and highlight some fantastic research that I’ve been involved in over the past few years. While I spend most of my time these days thinking about round goby invasion in the Great Lakes (see my last blog post

here), I have been involved in a few side projects throughout my time at Wayne State. One of the main questions I am addressing in my research with Michigan Sea Grant is how watershed quality (as influenced by human activities) affects the ability of invasive species to establish populations. To do this, I have looked at watersheds across the state, which reflect a gradient of overall quality. This means that I’ve spent a fair amount of time sampling in very urban and agricultural rivers that are highly impacted by human activities.

In contrast to the urban streams I am used to, I spent some time this month working on a long-term project in some streams that are about as remote as you can get in Michigan. My advisor,

Donna Kashian, has had research support and sponsorship from the

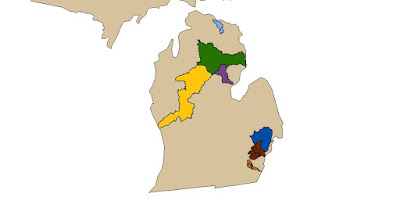

Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation (HMWF) in the Upper Peninsula (Figure 1) for about 11 years. The HMWF has been a fantastic group to work with and is truly a hidden gem in Michigan’s environmental research (if you’re interested, keep an eye out for their next

call for proposals). I was fortunate enough to be invited on these trips and have now been going for five years. The project was designed to develop a long-term monitoring program for ecosystem integrity in streams in the Huron Mountains (just west of Marquette in the UP). This area is quite remote and serves as a good "reference" location for tracking the impacts of human-mediated environmental changes like climate change, a newly constructed mine in the area, and general construction and development activities.

|

| Figure 1. General location of our sampling efforts in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (location indicated by red marker). Image: Google Maps |

Our project uses aquatic macroinvertebrates (Figure 2) to keep track of water quality in the area. Every July, we sample 30 streams in the area that are associated with varying levels of perturbations associated with human activities. In addition to macroinvertebrates, we take a suite of water quality samples: basic things like dissolved oxygen, pH, temperature, as well as samples we take back to the lab to process, like nutrients, metals, and organic carbon. The combination of these measures gives us an idea about if and how human activities might be affecting water quality in the surrounding area, and where there is the most impact. Collecting these types of data over a long timeframe (eleven years and counting!) provides a valuable resource in assessing how ecosystem integrity changes over time. It also provides clues as to the mechanisms for change based on the type of response observed in the data.

|

| Figure 2. My lab mate and fellow PhD student Darrin Hunt joined us this year. Here he is using a Hess stream bottom sampler to collect macroinvertebrates from one of our stream sites. At the end of the day, we sieve and preserve all our samples in ethanol to take back to our lab to process further. Pictured (bottom right) is a dragonfly nymph, a nice example of the invertebrates we collect. Photos: Corey Krabbenhoft |

Many of the streams we sample are much different than those you might be familiar with in the Lower Peninsula. Many are very small (less than one meter wide in some cases), only a handful of them regularly have fish, and they often have high levels of tannins due to leaf litter from the surrounding forest (Figure 3). Importantly, these streams are also free from the impacts of several invasive species which are common in the Lower Peninsula like dreissenid mussels (

quagga and

zebra mussels), and the

round goby, the species I work on in my research with Michigan Sea Grant. These streams are largely part of the Salmon Trout and Yellow Dog watersheds, both of which are important recreational trout fisheries in the area.

|

| Figure 3. Some of the more spectacular sites we sample every year. Photos: Corey Krabbenhoft |

So far, the majority of the impacts we have seen have been related to surface construction associated with development of the new mine in the area (Figure 4). In 2013, a year before mining operations commenced, we witnessed a dramatic restructuring of the road system through the area. What used to be single-lane dirt roads had been transformed into large two- to four-lane highways. Simultaneously, the bridges at stream crossings were redone to support the increased weight and frequency of logging trucks associated with the construction activities (and then ultimately the mining trucks themselves). This rapid and dramatic change to the riparian areas and bank stability was reflected in our invertebrate data by an increase in relatively tolerant invertebrate taxa (i.e., invertebrates that are sensitive to things like increased sedimentation were less abundant, while those that are relatively tolerant became more abundant) (Figure 5). The good news is that we saw a relatively quick recovery of the invertebrate communities the following year.

|

| Figure 4. Impacts observed due to construction activities. Left -- sediment barrier designed to keep excess silt from running into streams, which is almost completely buried. Middle -- a new culvert installed at one road crossing (my adviser, Donna Kashian, is pictured). Right -- unstable fill has resulted in wash-outs near some of the roads. Photos: Corey Krabbenhoft |

|

| Figure 5. Principal components analysis of the invertebrate communities for four of our most impacted sites over the course of the study. Each point represents the invertebrate community at a single site during a single year. All four sites are quite different in 2012 (yellow), largely due to a larger proportion of chironomids (midges), a particularly tolerant taxon. Image: Corey Krabbenhoft

|

This project is ongoing, and we hope to continue our monitoring efforts to develop a long-term data set for the area that can be used to detail the environmental consequences of discrete human activities, as well as general, long-term change (and how the degree of change in this remote area compares to that which we observe in more urban systems). As we continue processing samples, we will have a better understanding of any lasting consequences for the water quality in the area.

In the meantime, I’ll get back to daydreaming about round gobies and focus on my dissertation work. If you are interested to hear more about this project or want to chat about research in general, I’m more than happy to hear from you! You can find me at

ckrab@wayne.edu or on my Twitter page

@ckrabb.